By: Dr. Pranab Kr. Das, Assistant Professor, Department of Geography, Sree Chaitanya College, Habra

Courtesy: IANS/ Kuntal Chakraborty

Introduction:

India’s transport sector is large and diverse, catering to the needs of 1.4 billion people. In 2021, this sector contributed about 13-14% to the nation’s GDP, with road transportation holding a major share. Good physical connectivity in both urban and rural areas is essential for economic growth. Since the early 1990s, India’s growing economy has witnessed a rise in demand for transport infrastructure and services. Efficient and reliable urban transport systems are crucial for India to sustain high economic growth. The significance of urban transport in India stems from its role in reducing poverty by improving access to labour markets and thus increasing incomes in poorer communities. Services and manufacturing industries particularly concentrate around major urban areas, requiring efficient and reliable urban transport systems to move workers and connect production facilities to the logistics chain.

Factors Influencing Urban Mobility in India:

The factors influencing the mobility of urban population in Indian cities are rapid urbanisation, rising motorisation and dwindling modal share of Non-Motorised Transport (NMT). These factors have resulted in a sudden rise in the demand for travel. At the same time, the rapidly increasing levels of motor vehicle ownership and use have resulted in an alarming increase in negative externalities such as road congestion, air pollution, road fatalities, and social issues of equity and security.

Rapid Urbanisation:

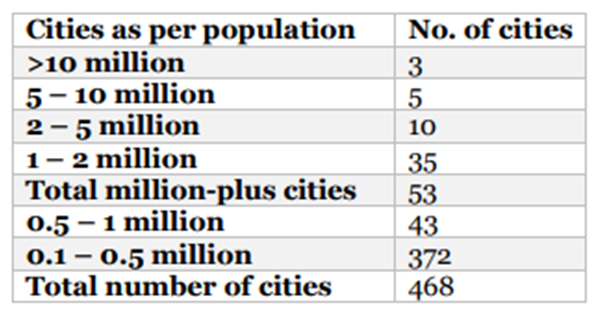

Rapid urbanisation is a challenge to urban mobility systems. In 1951, there were only five Indian cities with a population greater than one million and 42 cities with a population greater than 0.1 million, much of India effectively lived in villages. According to 2011 census data, there are three cities with a population of above 10 million and another 53 cities with an urban population greater than 1 million and 468 cities with a population above 0.1 million (See Table 1).

Table 1: Number of cities as per population; Population figures as per 2011 census

Between 2001 and 2011, India’s urban population increased from 286 million to 377 million, among these, nearly 50% live in small cities (> 0.5 million). Between 2011 and 2021, it is estimated that 498 million (35.39%) Indians live in urban areas. The fastest decadal growth was observed in cities with populations between 100,000 and 1 million, such as Surat, Nashik and Faridabad, while metro cities like Mumbai, Delhi, Kolkata, Chennai, Hyderabad and Bengaluru experienced slower peripheral growth with neighbouring villages surrounding the core city merging with the larger metropolitan area. The top 10 Indian cities with 8 per cent of the total Indian population are estimated to contribute 15 per cent to the country’s GDP output while the remaining 53 cities with a million-plus population contribute 31 per cent of the Indian GDP. At present more than 35% of people live in 8,000 cities and towns. This rural-to-urban demographic transition is expected to result in a jump in urban population to around 600 million people by 2031, which constitutes almost 40 per cent of the Indian population.

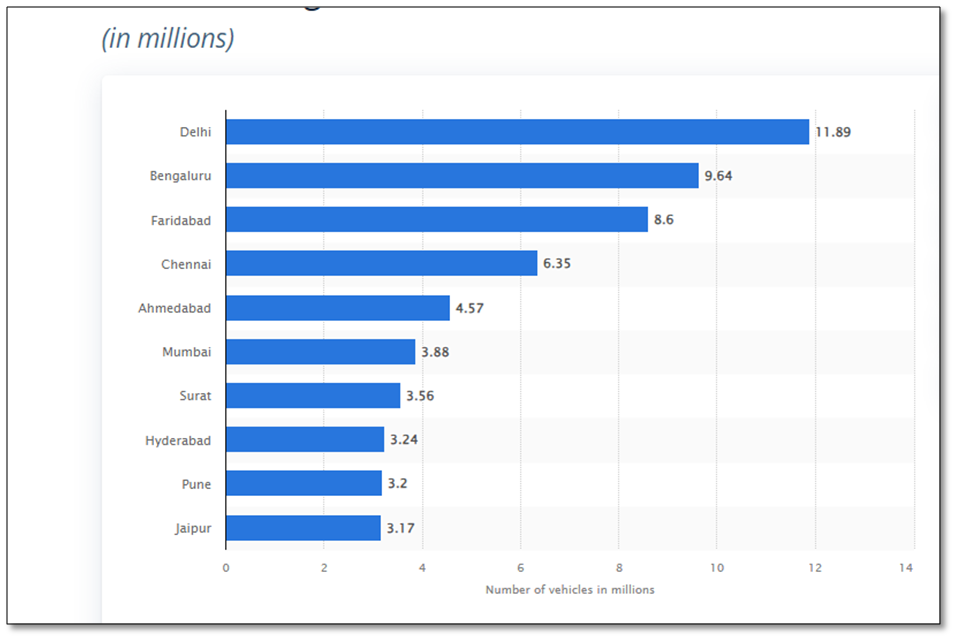

Since 2001, the number of vehicles per 1,000 people in Indian metropolitan cities has grown significantly. The total registered vehicles in the country grew by 9.8 % (Compounded Annual Growth Rate) between 1991 and 2009. Meanwhile, total vehicle registrations in metro cities grew at almost double rates in million-plus cities. In 2019- 20, cities posted a CAGR of 9.83 % in the total number of vehicle registrations or a share of nearly 32 per cent (104.41 million) of the total vehicles in the country (326.3 million). 10 cities have vehicle higher registration rates compare to other cities in India in 2020. Their combined registration was 58.40 million or 17.89% of the total registration of the country. Delhi had the highest vehicle population with almost 11.89 million in 2020. However, in 2023 Bengaluru has suppressed Delhi in terms of private vehicles i.e. 23.1 lakhs. In the coming decades, cities and towns are expected high influx of vehicular movements.

Fig: Number of Registered vehicles in major Indian cities

Decreasing share of Non-motorised Transportation:

Non-Motorised Transportation (NMT), also known as Active Transportation, includes walking, bicycling, cycle rickshaw, and wheelchair travel. In Indian cities, people who commute by walking outnumber those who use private motorised transport. As cities sprawl, the share of NMT reduces drastically creating increased reliance on private modes of transport. Urban design that fosters walking and cycling is under threat as sprawl-based urban design is becoming the norm in big cities. The plans for new extensions and townships are still based on low-density, segregated land use with wide roads.

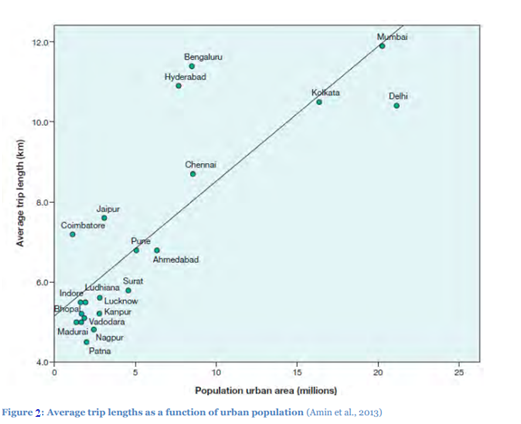

In megacities with more than 10 million populations, average travel distances have increased up to 9-12 km. Cities with 2-5 million populations such as Pune, Surat, Kanpur, etc. have an average trip distance of around 6 km with a high NMT share of 40 to 50 per cent. This share further increases to 60 to 70 per cent in cities with population between 1 and 2 million. Smaller cities have a higher threat of losing walking and cycling share to private motorised transport in the coming decades. These cities have neither invested in infrastructure for NMT nor have a formal public transport alternative to prevent a shift to personal transport modes. Sidewalks and cycle tracks are the most neglected in infrastructure planning. The city’s poor are captive users of walking and cycling, but most neighbourhoods have either poorly constructed footpaths or they have been badly maintained, while some have no footpaths at all. The city’s poor are the most affected.

Urban Transport Problems:

a) Road congestion:

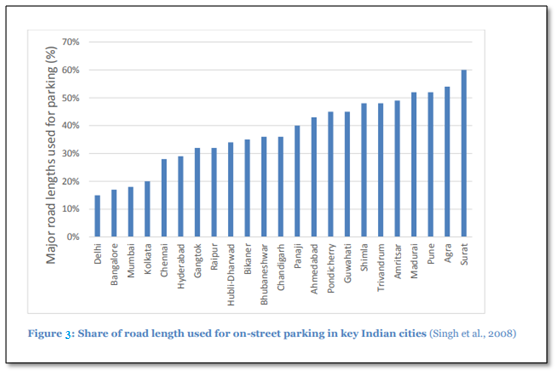

As populations increase, the average travel distances as well as intensity are expected to increase as there is a direct correlation between the two indicators (See Figure 3). Average trips lengths for 6 metro cities of India are over 8 km, while it is 6 km or less for all other million cities. This trend in trip length and frequency is only expected to increase with increasing income levels, migration, participation of women and a service-oriented economy. As more people travel over longer distances on regular basis for employment and education purposes, will inevitably lead to road congestion.

b) Parking problems:

The acute shortage of parking spaces both on and off the streets in Indian cities increases the time spent searching for a parking spot and induces traffic congestion. Available data shows that a high proportion of Indian streets are faced with on-street parking issues. This problem is especially acute in smaller, compact Indian cities. Delhi has 14 per cent of road lengths used for on-street parking while Surat has almost 60 per cent of its road lengths blocked by on-street parking. On-street parking is perversely incentivized because it is either free or priced lower than off-street parking. Even if cities invest in multilevel car parks in prime areas, the parking rates are not expected to recover the costs.

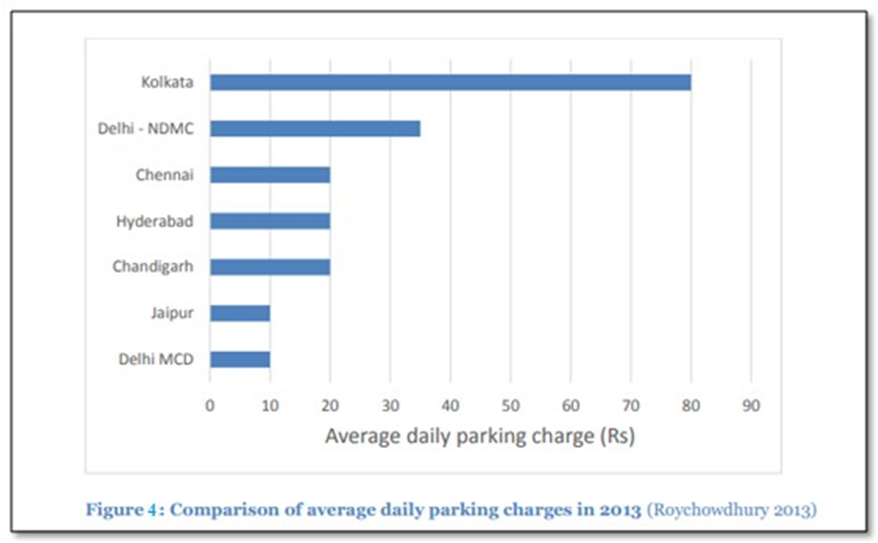

In Delhi, the public parking charges are fixed as low as Rs.10 for 8 hours during the daytime when it should be at least Rs.40 per hour. Kolkata has the highest parking charges in India and these charges are time and place variable, i.e. higher parking charges in specific commercial zones and the rates increase by the hours. In Kolkata, a car pays Rs. 80 for eight hours of parking during daytime, while in Delhi MCD region; car parking charges are as low as Rs.10 for up to 10 hours of parking. Figure 5 shows the eight-hour average parking rates in different cities but does not include special parking rates in parking spaces like malls, airports, etc. Unless parking issues are addressed through a systematic planning process and strict enforcement, such issues will only exacerbate over time in Indian cities.

Even in the densest Indian cities like Mumbai, Kolkata, Chennai and Delhi, cars (typical spot = 280 sq. ft.) occupy more space than a family of four (range from 85-250 sq. ft. depending on income level). In several Indian cities, commercial development of vacant plots has taken place without following systematic planning procedures for access and mixed-use. This induces heavy traffic leading to localized congestion and parking issues in the neighbourhood.

c) Air pollution:

According to available air quality data of 180 Indian cities, there is a wide variation in the pollution concentration and severity across cities. Cities are considered critically polluted if the levels of criteria pollutants (namely PM10 and NO2) are more than 1.5 times the standard. Results show that half of the residential areas in cities monitored by CPCB are at critical levels of air pollution. According to the US-based Health Effects Institute, people residing within 500 metres from roads are exposed to vehicular fumes.

Air pollution in Indian cities is the fifth leading cause of death in India. Annually, about 620,000 premature deaths occur due to air pollution in Indian cities. Premature deaths due to air pollution occur as a consequence of cardio-vascular ailments. Over a decade, air quality management attempts have met with mixed responses. Metro cities that have initiated pollution control action have witnessed either stabilization or dip in the pollution levels, however, in other cities, the situation has been observed to be getting worse. Toxic air and its effects on health are seriously compromising the ‘livability’ of Indian cities.

In the case of Delhi, vehicular pollution started deteriorating in 1990. While the number of vehicles grew by 87% to 3.6 million between 1990-2001, the city’s population increased by merely 14% from 9.5 to 13.8 million in the same period. The Supreme Court of India responded by a ruling in 1998 that all public transport should shift from the use of diesel to CNG by March 31, 2001. After repeated deferments, the court imposed the order that all buses be converted to CNG by December 2002. Similarly, on 18 July, 2008 the Calcutta High Court mandated that all smoke-belching petrol auto rickshaws (hereafter referred to as autos) be replaced by Liquified Petroleum Gas (LPG) fuelled autos. This was hailed as a success story; however, the results did not indicate an all-round improvement in ambient air quality as the amount of NOx rose along with a marginal decrease in PM10.

d) Deteriorating road safety:

The high dependence of migrants on non-motorised transport modes such as walking and cycling causes traffic mix in common roads where fast-moving motorised traffic shares the roads that leading to road accidents (WHO, 2013). In most Indian cities, non-motorised modes presently share the same road with cars and two-wheelers leading to unsafe conditions for all (National Urban Transport Policy (NUTP), 2008).

The percentage of streets with pedestrian pathways is hardly 30 per cent in most Indian cities. Pedestrian fatalities constitute a significant share of total in absence of adequate pedestrian facilities. In New Delhi, Bengaluru and Kolkata, the pedestrian fatality share is greater than 40 per cent. In the case of Bengaluru, three pedestrians are killed on roads every two days and more than 10,000 are hospitalised annually. Elderly people and school children carry a large share of the burden with 23 per cent fatalities and 25 per cent injuries. The main reason behind this is an inequitable distribution of road space and the fact that streets in India are not designed to accommodate all the functions of a street. Furthermore, only a part of the right of way is developed leading to unorganised and unregulated traffic, which is unsafe for pedestrians and cyclists.

Policy responses to address urban transport issues:

The role of the central government in urban transport is still confined to a few dimensions. Until the mid-1990s, connectivity of rural areas to urban centres of India remained the main focus of investment and transport policy direction, since a majority of the population lived in rural areas (Tiwari, 2011). Most large cities are able to make decisions and implement them at the local level. But they do not have the right incentives to make strategic decisions in the long-term interest of cities and its inhabitants. There are also no checks and balances to ensure that a good strategic plan gets implemented. Central monitoring and supervision are limited at the local level where planning and policy is carried out. This situation has created an institutional gap reflected in the slow transfer of powers and resources from states to local governments. The political constituencies of state and local institutions being different, the continued dominance of the state produces transport policies that are not aligned with local interests. The following subsections highlight the main plans, strategies and programs initiated by the central government to address urban transport challenges in Indian cities.

National Urban Transport Policy (NUTP):

The central government, under the Ministry of Urban Development (MOUD), issued the National Urban Transport Policy in 2006 with specific policy objectives of achieving safe, affordable, quick, comfortable, reliable and sustainable access to jobs, education, shopping and recreation and other such needs to an increasing number of urban residents within our cities. The policy acknowledged problems of road congestion and associated air pollution. To address these issues, the NUTP proposed four strategies primarily focusing on increasing the efficiency of road space by favouring public transport, using traffic management instruments to improve traffic performance, restraining the growth of private vehicular traffic and technological improvements in vehicles and fuels to reduce vehicle emissions. The NUTP recognized the states as the main facilitators in the process of policy implementation and the central government’s role was confined to supporting the states with the necessary financial support and technical expertise. Without land use transport integration on the ground and specific policies and action plans supporting the same, not much change in the existing urban transport condition can be expected. Even today, appropriate accessibility and mobility objectives are not well-considered and defined in land development and as a result current development practices tends to lengthen trips and leads to increased congestion. Real estate developers have continued to build new developments with segregated land uses and in locations that are inaccessible by PT and NMT. Violation of zone laws is a common occurrence which often translates to a different land use pattern emerging than what was planned. This adversely impacts transport and traffic patterns, which is nowhere near the one that was expected. Even with specialised institutions to deal with these issues, the haphazard land development continues due to irrelevant considerations. Although the NUTP supports the integration of land use and transport, it only touches on the generalities associated with it (Sriraman, 2012). NUTP’s silence on ways in which national and state leadership can help city governments integrate land use and transport in urban development is criticised. International experience has shown that participatory approaches that incorporate community consultation and wider participation by all social groups have been successful in enhancing sustainable urban transport development. Such “bottom-up” approaches are more likely to win public support, especially when difficult policy decisions arise, such as while implementing transport demand management measures. This approach has been visibly absent in the NUTP. It would require a fundamental institutional change in the planning process to incorporate participatory approaches in decision making and seek interdisciplinary solutions to urban transport problems. It has been well recognized in the NUTP that a solution to complex urban transport problems lies in the development of an efficient and affordable PT system. The fare issue is not addressed in a comprehensive manner that would allow a full range of options to be considered. This could be in the form of targeted user subsidies such as cash transfers or direct financial assistance to poor travellers.

Jawaharlal Nehru National Urban Renewal Mission (JNNURM):

The Jawaharlal Nehru National Urban Renewal Mission (JNNURM) was set up in December 2005 by the central government, and 63 cities were identified to be eligible for seeking central funds under this program for urban renewal and reforms in phase one.

Objectives:

- Its prime objective was to create empowered and financially sustainable Urban Local Bodies (ULBs) for successfully managing the local urban issues.

- Another objective was to address distortions in the urban land markets arising largely out of a plethora of regulations.

To achieve these objectives, the JNNURM mandated a set of reforms at the state and municipal levels. The urban transport sector was allocated 11 % of the total JNNURM investment. Except for Delhi, most urban transport systems and interventions are funded and owned by state governments. The JNNURM program attempted to improve the public transport system in larger cities through funding of public transport buses, development of comprehensive city mobility plans and supporting city transport infrastructure projects. Up to December 2012, 15,388 buses, at a cost of more than Rs.47 billion, in 63 cities had been funded under the program. This has led cities to develop new bus services. Bus rapid transit projects have been initiated in 10 large cities. Some cities have also used central funding to improve traffic management.

To encourage the holistically planned development of cities, the JNNURM program mandated the preparation of City Development Plans (CDP). The CDP would highlight the city-level improvements so as to integrate land use and transport planning and address infrastructure needs in a sustainable manner. Moreover, JNNURM required that all proposed transport projects comply with the NUTP guidelines. To give effect to this, the program provided for an outlay of central assistance of more than Rs. 66,000 crore for the seven-year period, and linked the release of assistance to completion of the reforms. Currently, 138 urban transport projects have been approved, with the majority (80 per cent) in Category A cities with populations of at least four million.

Faster Adoption and Manufacturing of (Hybrid and) Electric Vehicles (FAME):

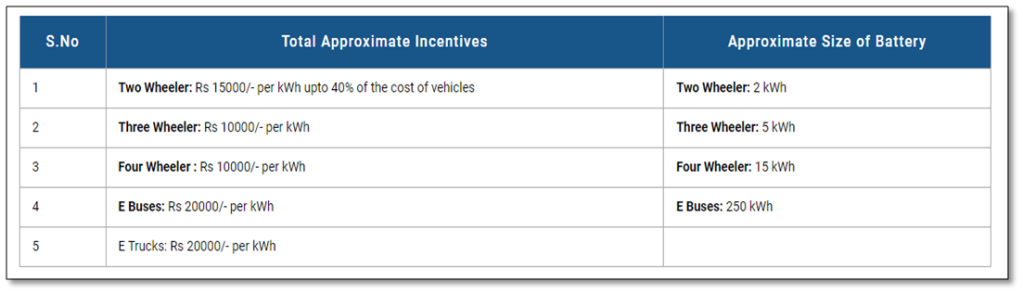

FAME, or Faster Adoption and Manufacturing of (Hybrid and) Electric vehicles, is currently India’s flagship scheme for promoting electric mobility. It was launched in 2015. Currently, in its 2nd phase of implementation, FAME-II is being implemented for a period of 3 years, eff. 1st April 2019 with a budget allocation of 10,000 Cr which includes a spillover from FAME-I of Rs 366 Cr to ensure smart mobility across the country, especially in urban areas. The incentives offered in the scheme are:

Table 2 : Amount Intensives on different EVs

Source: https://e-amrit.niti.gov.in/national-level-policy

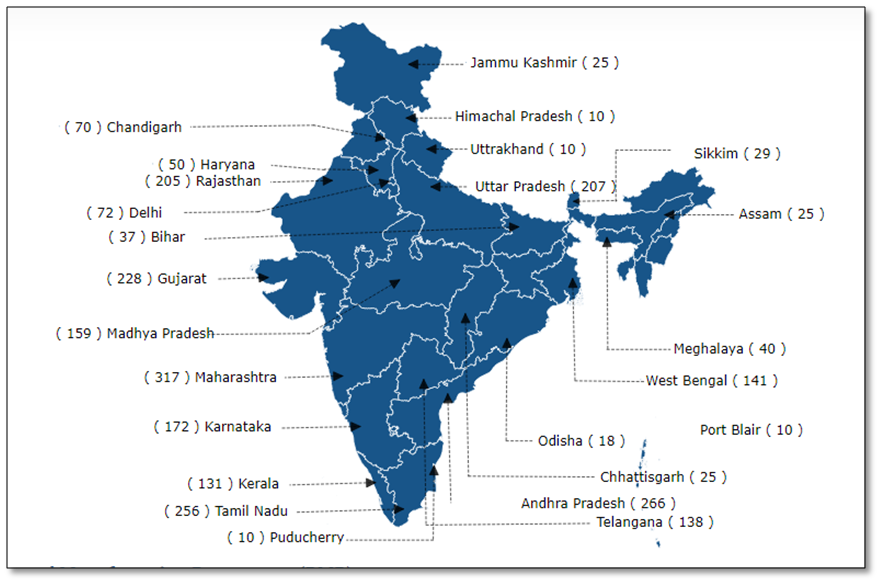

The Department of Heavy Industries has also sanctioned 2636 charging stations in 62 cities across 24 States/UTs under the FAME India scheme phase II. State-wise allocation of these charging stations is as follows:

Map 1: Location of EVs charging stations across India.

Source: e-Amrit/ Nitiayog

Bibliography :

Agarwal, O.P., 2006. Urban transport. In: A. Rastogi, ed. India Infrastructure Report 2006 – Urban Infrastructure. Oxford University Press, pp. 106–129. Available at: http://www.idfc.com/pdf/report/IIR-2006.pdf.

Ahluwalia, I.J., 2011. Report on Indian Urban Infrastructure and Services The High Powered Expert Committee. Available at: http://icrier.org/pdf/FinalReport-hpec.pdf.

Amin, A. et al., 2013. Planning and design for sustainable urban mobility – Global Report on Human Settlements 2013, UN Habitat. Available at: https://unhabitat.org/global-report-on-human-settlements-2013.

Estache, A., 2007. Infrastructure: A survey of recent and upcoming issues. In: Annual World Bank Conference on Development Economics. World Bank, Washington D.C., pp. 47–82. Available at: http://siteresources.worldbank.org/INTDECABCTOK2006/Resources/Antonio_Estache_Infrastructure_for_Growth.pdf [Accessed May 2, 2024].

Baindur, D., 2011. Planning Sustainable Urban Transport System – Case Study of Bengaluru Metropolitan Region. Journal of Economic Policy and Research, 7(1).

Bhatt, C. et al., 2013. Sustainable Urban Transport – Principles and implementation guidelines for Indian cities. Available at: http://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/index.php?page=view&type=400&nr=865&menu=151

Rangarajan, C., Dev, S.M. & Sundaram, K., 2014. Report of the Expert Group to review the methodology for measurement of poverty. Available at: http://planningcommission.nic.in/reports/genrep/pov_rep0707.pdf.

Chanchani, R. & Rajkotia, F., 2011. Traffic study at Mantri Square Mall, Malleshwaram. Centre of infrastructure, Sustainable Transportation & Urban Planning (CiSTUP). Available at: http://cistup.iisc.ernet.in/radha/planner_images/TrafficStudy@MantriMall_Report.pdf [Accessed April 25, 2024].

Chotani, M.L., 2010. A Critique on Comprehensive Mobility Plan for the City. In: Urban Mobility India Conference and Exhibition.

Planning Commission, Transport Division, New Delhi. Report of the Working Group On Logistics. Available at: http://planningcommission.nic.in/reports/genrep/rep_logistics.pdf.

CSE, 2014. EPCA Report on priority measures to reduce air pollution and protect public health – In the matter of W.P. (C) No.13029 of 1985; M.C. Mehta v/s UOI & others. Available at: http://cseindia.org/userfiles/EPCA_report.pdf [Accessed May 7, 2024].

Foster, A. & Kumar, N., 2007. Have CNG Regulations in Delhi Done Their Job? Economic and Political Weekly, XLII(51). Available at: http://www.epw.in/special-articles/have-cng-regulations-delhi-done-their-job.html.

Gauthier, A., 2012. San Francisco Knows How to Park It.

Agarwal, O.P., 2006. Urban transport. In: A. Rastogi, ed. India Infrastructure Report 2006 – Urban Infrastructure. Oxford University Press, pp. 106–129. Available at: http://www.idfc.com/pdf/report/IIR-2006.pdf.

Ahluwalia, I.J., 2011. Report on Indian Urban Infrastructure and Services The High Powered Expert Committee. Available at: http://icrier.org/pdf/FinalReport-hpec.pdf.

Amin, A. et al., 2013. Planning and design for sustainable urban mobility – Global Report on Human Settlements 2013, UN Habitat. Available at: https://unhabitat.org/global-report-on-human-settlements-2013.

Estache, A., 2007. Infrastructure: A survey of recent and upcoming issues. In: Annual World Bank Conference on Development Economics. World Bank, Washington D.C., pp. 47–82. Available at: http://siteresources.worldbank.org/INTDECABCTOK2006/Resources/Antonio_Estache_Infrastructure_for_Growth.pdf [Accessed May 2, 2024].

Baindur, D., 2011. Planning Sustainable Urban Transport System – Case Study of Bengaluru Metropolitan Region. Journal of Economic Policy and Research, 7(1).

Bhatt, C. et al., 2013. Sustainable Urban Transport – Principles and implementation guidelines for Indian cities. Available at: http://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/index.php?page=view&type=400&nr=865&menu=1515.

Rangarajan, C., Dev, S.M. & Sundaram, K., 2014. Report of the Expert Group to review the methodology for measurement of poverty. Available at: http://planningcommission.nic.in/reports/genrep/pov_rep0707.pdf.

Chanchani, R. & Rajkotia, F., 2011. Traffic study at Mantri Square Mall, Malleshwaram. Centre of Infrastructure, Sustainable Transportation & Urban Planning (CiSTUP). Available at: http://cistup.iisc.ernet.in/radha/planner_images/TrafficStudy@MantriMall_Report.pdf [Accessed February 25, 2014].

Chotani, M.L., 2010. A Critique on Comprehensive Mobility Plan for the City. In: Urban Mobility India Conference and Exhibition.

Planning Commission, Transport Division, New Delhi. Report of the Working Group On Logistics. Available at: http://planningcommission.nic.in/reports/genrep/rep_logistics.pdf.

CSE, 2014. EPCA Report on priority measures to reduce air pollution and protect public health – In the matter of W.P. (C) No.13029 of 1985; M.C. Mehta v/s UOI & others. Available at: http://cseindia.org/userfiles/EPCA_report.pdf [Accessed March 7, 2014].

Foster, A. & Kumar, N., 2007. Have CNG Regulations in Delhi Done Their Job? Economic and Political Weekly, XLII(51). Available at: http://www.epw.in/special-articles/have-cng-regulations-delhi-done-their-job.html.

Gauthier, A., 2012. San Francisco Knows How to Park It.

Sarma, K. Sen et al., 2011. Road Transport Year Book (2007-2009) Volume 1. Ministry of Road Transport and Highways, Government of India.

Singh, V. et al., 2008. Study on Traffic and Transportation Policies and strategies in urban areas in India. Available at: http://urbanindia.nic.in/programme/ut/final_Report.pdf.

Sriraman, S., 2012. The need for a new orientation to the National Urban Transport Policy. In: R. Jha & J. Chandiramani, eds. Perspectives in Urban Development: Issues in Infrastructure Planning and Governance. Capital Publishing Company.